BRUSSELS, Belgium — The assignment given to the Belgian police in the summer of 2014 was straightforward but high stakes: Follow two men suspected of involvement with ISIS through the streets of Brussels. Find out who they meet, record what they say. A court had approved wiretaps for the men’s phones and for the use of tracking devices, and a specialized team of covert operators from the secret service had broken into the men’s homes and vehicles and planted bugs and GPS devices without leaving a trace.

Rather unusually, there had been little problem getting senior police officials and the courts that oversee Belgium’s personal privacy laws to approve the mission. Partly, it was the two men's history: They had long criminal records — drug dealing, petty theft, and the occasional violent robbery — and now, unbeknownst to them, had been placed on a terrorism watch list.

With hundreds of people suspected of having ties to ISIS and al-Qaeda, it would be impossible for the Belgian authorities to monitor all of them. But these two were believed to be linked to Mehdi Nemmouche, a 29-year-old French-Algerian man charged with killing four people at the Jewish Museum of Brussels on May 24, 2014.

Belgian authorities knew there had been an alarming increase in violent rhetoric — as evidenced by the proliferation of online videos and public demonstrations, and by the criminal trials of members of Sharia4Belgium, a group advocating extremist ideology — much of it linked to the rise of ISIS in Syria and Iraq. But even for trained investigators, let alone police officers typically assigned to financial fraud or money-laundering cases, getting an overall sense of what was happening remained elusive.

In part this was because of the transformation in the threat posed by ISIS militants; as nebulous as al-Qaeda had been, it was at least an organization with a defined leadership and network of followers. These new cases were much more challenging, seemingly organic in nature, with a more diffuse structure that was nearly impossible to pin down.

The cops hoped that the surveillance of the two suspects would shed light on what they feared was a new kind of international jihadist cell in the heart of the European Union’s previously sleepy capital.

“The system was finally somewhat working,” one of the cops who had been tailing the two men told me when we met in a café in Brussels two years later. He was half explaining to me and half trying to make his own sense of what happened, at a time when Europe — and France and Belgium in particular — was being convulsed by repeated terrorist attacks.

“We’d gotten the approval to place electronic surveillance all over these guys,” said the cop, who remains assigned to counterterrorism operations and cannot be identified. “That itself was pretty rare back then. And our covert teams had gotten in and wired them up without being seen. We even had the resources for once to follow them around the clock. It was as good an operation as we have ever set up, and we expected great things from it.”

As the suspects’ car weaved through Brussels’ workday traffic, the cops felt they could relax a bit. Normally, a proper surveillance effort for a suspect requires as many as 20 police officers to watch without being seen. But with tracking and listening devices in the cars and homes of the suspects, the police could simply follow at a safe distance and observe.

“It was going great until they switched from French to Arabic.”

“It was going great until they switched from French to Arabic,” said the cop. “At that stage we lost everything. Do you know how long it takes us to get a translation [of a tape] into French from Arabic?”

In this case: three days, but by then they were gone.

“And that was pretty good because officials were motivated. It could be as little as 24 hours if we thought they were literally on the verge of an attack, but three days, one day, whatever — it’s too long.”

By the time translators had prepared a transcript, the men had fled Brussels by train for another European city — the officer refused to say which one — and eventually flew to Istanbul, where they easily made their way to southern Turkey and across the border into parts of Syria then controlled by ISIS.

Like thousands of other militant believers in jihadist ideology, they’d immigrated to the burgeoning proto-caliphate and abandoned their old lives in the “lands of the unbelievers.” In doing so, they disappeared from the eyes of an increasingly worried intelligence community, where many analysts were convinced citizens turned militants would return from training camps in Syria to exploit Europe’s open society and carry out attacks on the continent.

Since 2010, the Belgian and French authorities have been faced with a jihadist problem both more entrenched at home and more deeply interconnected to the international scene than had been previously understood. After last November’s attack on Paris, in which 130 people were killed, the full extent of the problem — not just for Belgium and France, but for the European Union — become tragically clear: An international network has exploited inherent security weaknesses of the EU's open borders and brought French-speaking militants from Europe into the forefront of international terrorism. Between 2011 and the end of 2015, an estimated 12,000 people from 81 countries joined ISIS in Syria and Iraq, including 1,700 French and almost 500 Belgian residents, according to a comprehensive study of foreign fighters by the Soufan Group. The French S list — a database of suspected extremists and security threats — has grown to nearly 10,000 people, and those are only the people who have been identified.

ISIS militants threaten Europe with a wave of violence not seen since the heyday of 1970s political terrorism, and it appears to have the potential to be far more deadly. Previous terror campaigns led by Ireland’s IRA, Spain's ETA, and Italy's Red Brigades tended to have national aspirations and couldn't exploit total freedom of movement between European countries. Those groups also had political considerations and patrons that forced them to calibrate their violence.

Nativist politicians from Republican presidential nominee Donald Trump to National Front leader Marine le Pen in France play up the notion of ISIS as an existential threat to capitalize on fears about terrorism. All the while, European counterterrorism officials seem overwhelmed by the thousands of names of suspects, stymied by a lack of integration across the EU, and caught on the hoof by perpetrators who often appear to lack any prior extremist links. And in the towns and cities where new jihadists are being recruited and cultivated most fervently, authorities lack the kind of surveillance techniques deployed by their American counterparts.

As the spring and summer of 2016 progressed with attacks and arrests across Europe — at one point in France, Belgium, and Germany, almost weekly — I met with investigators as they struggled to make sense of the new phenomenon, shuttling between crimes that had already happened and struggling to prevent new attacks.

This is what terrorism investigations in Europe look like today.

Samia Maktouf entered a small conference room in her chic Paris law office, holding a bundle of papers that contained a huge amount of information on ISIS’s international networks.

A French-Tunisian dual citizen, Maktouf works from her law firm on a classic Paris street not far from the Champs-Élysées. A member of the International Criminal Court’s bar, she moves easily between French, Arabic, and English, which serves her well as one of France’s most famous victim advocates, specializing in international terrorism. Precise in her language, she nonetheless sounded livid about the slow release of information by the government that she said hinders her work representing the victims of terror attacks in France and Tunisia, serving as their advocate in the official investigations.

“They’re covering something up,” she said of the investigations into the Paris attacks.

Maktouf is well-aware of the threat posed by this new era. ISIS makes its goals clear via social media and slickly produced propaganda videos: It wants a clash of civilizations that will force both Muslims and non-Muslims to accept that coexistence in Europe isn’t possible. France, with both the largest Muslim population in Europe, at over 6 million people, and a popular xenophobic right-wing political movement led by Marine le Pen, regularly figures in the exhortations of the group and its spokesmen, who often address the issue in French-language videos and online magazines.

Maktouf laid out the connections between various ISIS attacks, across both North Africa and Europe, which she has uncovered through the immense database she has built up on Francophone jihadists since she started investigating in 2010. The repeated links among the attackers have led her to believe that a handful of key figures in the ISIS hierarchy direct most of the international violence, with the European leadership mostly drawn from French-speaking countries.

“The Paris attack was committed by a Belgian cell, we know that,” she said, showing me a hand-drawn chart detailing the connections between people suspected of involvement in about a dozen successful or attempted attacks across France and Belgium since 2010.

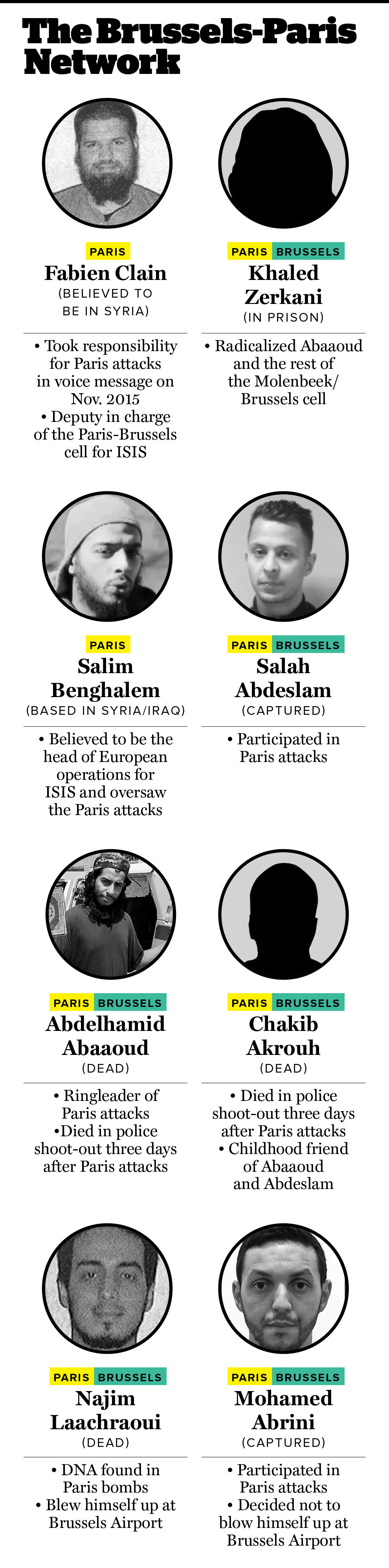

The chart was filled with names, dates, and places that are all too familiar: the Bataclan in Paris, Verviers in Belgium, the Jewish Museum of Belgium in Brussels, and the suicide attacks in March that killed 32 people across the Belgian capital. And two men repeatedly connect to the others. The first is well-known from last November’s massacres in Paris: Abdelhamid Abaaoud, who masterminded the operations around the city that killed 130 people and died in a shoot-out with French police five days later. But Paris wasn’t his first attempt at international terrorism: Investigators put him at the center of at least half a dozen smaller or unsuccessful plots since he returned to Europe from ISIS-held territory in late 2014.

The second name isn’t as infamous as Abaaoud’s, but Maktouf argued he’s a more important figure: Fabien Clain, a 40-year-old French convert to Islam now believed to be in Syria or Iraq. It was Clain’s voice, in a recording released online by ISIS, that took credit for the operation. But according to Maktouf and French investigators, his role wasn’t limited to public relations as the voice of the massacre — he is in fact a leading figure inside ISIS’s foreign operations department.

“The Paris and Brussels attacks were directed by Clain,” said Maktouf, pointing at the direct personal links between him and virtually every attack undertaken in France since 2010. “Abaaoud was the man on the ground but … Clain ran the operation.”

Maktouf has been fighting hard to get French authorities to reveal more information about Clain. She wants to find out more about his role in attacks ranging from Brussels and Paris to the 2012 killing spree by al-Qaeda’s Mohammed Merah, which killed seven people, including schoolchildren, in Toulouse. But French authorities have so far rebuffed her requests, citing national security and intelligence concerns.

Clain had first drawn the attention of authorities when he returned to France in 2004, having studied Islam and Arabic in Cairo. He quickly garnered respect within militant circles for his religious scholarship and command of radical Islamic jurisprudence, and in 2009, a French court convicted him of recruiting fighters for al-Qaeda in Iraq, the precursor to ISIS. Upon his release from prison in 2014, he somehow managed to slip away from house arrest and is believed to have escaped to Syria and joined ISIS.

The opaque nature of ISIS’s command structure makes it almost impossible for investigators to know the exact nature of each person’s role. But a French intelligence official and Belgian investigators told me that Clain is now thought to be a top deputy of Salim Benghalem, a French-born jihadist increasingly believed to command European operations for ISIS from Syria. Benghalem — who has called on French-speaking Muslims to support the proto-caliphate via online videos — is himself thought to have risen to an operational command role after starting out as a guard of Western hostages in Raqqa, ISIS’s self-proclaimed capital in Syria.

In stark terms: Clain, Abaaoud, and Benghalem connect to every single successful or failed terror attack in France or Belgium in the last 10 years, according to the chart in Maktouf’s office.

Maktouf also told me something that wasn’t known to the Belgian investigators with whom I was talking. She has discovered that before he went to Cairo in 2004, Clain had lived in the central Brussels neighborhood of Molenbeek — a mainly immigrant and heavily Muslim suburb where the Paris attackers plotted the massacre. It was here, investigators believe, where he became an associate of another senior figure — Khalid Zerkani, a street preacher dubbed “Papa Noel” by the media for his Santa-style beard. In April, a Belgian court sentenced Zerkani to 15 years in prison for radicalizing and sending fighters to Iraq and Syria.

A French intelligence official confirmed to me that a link between Clain and Zerkani was formed back then in Molenbeek, and that it could provide the origin story for one of the most dangerous terror cells in Europe’s history — the Brussels cell that masterminded the Paris and Belgian attacks.

Zerkani’s influence is at the heart of this cell. According to sealed sentencing documents obtained by BuzzFeed News, Zerkani’s recruits included Abaaoud, seen as his star pupil, as well as both Najim Laachraoui and Mohamed Abrini — suspects in both the Paris and Brussels attacks.

A week after speaking with the official, I went to a café in the Belgian capital to meet with a member of the security service to ask him about Clain’s role in the Brussels cell. Clain’s name was well-known to the authorities because of the ISIS statement he issued on the Paris attacks, but the security official I spoke to didn’t seem to make the connection to Brussels until I told him that Clain briefly lived in Molenbeek and knew Zerkani.

“Shit,” he said, taking a sip of his whiskey. “That wouldn’t surprise me at all. It makes sense.”

The construction of the Brussels cell reveals how ISIS manipulates criminal mentality in its recruiting and exploits existing underground networks in the heart of the EU to carry out its attacks. Its members were mostly small-time thieves and drug dealers who had been converted to the radical cause by Zerkani.

But the operations carried out by the Brussels cell also reveal how ISIS is capable of taking advantage of the political climate in Europe. Nine attackers carried out the Paris attack, seven of whom have been identified as EU citizens. At least six of them are thought to have traveled to Syria, and then exploited the migrant exodus as cover to re-enter Europe under false names. ISIS had even gone so far as to falsely announce Abdelhamid Abaaoud’s death in Syria in early 2014, shortly before he returned to Europe using faked paperwork.

Not a single European security official would tell me when exactly they realized Abaaoud was in fact still alive and planning attacks in Europe. But by the time of the Paris attacks in November 2015, they were well-aware that he was walking free around Europe and involved in planning operations. Wiretaps and phone intercepts confirmed that he was in contact with other jihadists, but authorities had no idea where he was. Despite an international arrest warrant, he was able to move around as he pleased.

“The police blew it.”

A Belgian military intelligence officer told me earlier this summer that he had tried to track Abaaoud using NATO surveillance in Syria and Iraq, but got nowhere. And he was angry at the bureaucratic chaos at the heart of EU counterterrorism efforts: Member states would file notices with Interpol or Europol about dangerous radicals, but then leave the investigations to be conducted locally on an ad hoc basis. There was no joined-up thinking, he said.

“The police blew it,” said the operative, who works internationally undercover in the Middle East and Africa on terrorism and organized crime issues. “That [Abaaoud] was able to get back in [from Syria] and run things in Brussels, Paris, shows up the UK in August and is seemingly everywhere moving freely … inexcusable.”

The authorities’ inability to keep track of Abaaoud’s movements is indicative of the complexity of counterterrorism challenges presented by an underworld in which gangsters, jihadists, and ex-convicts come together to share false paperwork, contacts, and safe houses. Abaaoud and his friends were comfortable walking the constantly shifting line between newly minted jihadists and small-time criminals dealing drugs, stealing cars, and selling weapons.

Infiltrating criminal organizations in this world is nearly impossible given their diffuse nature, but sometimes even language is an obstacle. Each European city has developed its own Arabic dialect among local teens and young men, which even fluent speakers can have trouble understanding. Police translators who are comfortable listening to a wiretap of targets from Brussels describe the nightmare of trying to understand a cell based in Antwerp, or outside of Paris.

And there’s little in police textbooks on how to identify suspects in the new jihadist environment, typically but not always first- or second- generation Belgians of North African descent, who often have little religious education or history of piety. If the militants’ own families are often caught off guard by the sudden transition to extremism, police have had little luck predicting who might make the jump from petty crime to brutal ideological murders. And given that so much of the radicalization happens online, or among small groups of friends hanging out together in tight-knit neighborhoods, it is very difficult for police to monitor.

One Belgian investigator tried to explain how ephemeral the situation feels, and how hard it is to distinguish between a criminal and a jihadist, when he described the behavior of a young militant who had returned home after fighting with ISIS. “We have one guy who comes home from Syria to visit people on breaks,” he said. “We know he’s in Syria and he’ll sneak back into the town, see his friends, and go clubbing. We have CCTV of him sniffing lines of coke and drinking in a club on one break before he goes back to Syria.”

The investigator said it felt like he was watching a tape of a soldier on R&R. The kid can take drugs, drink, and have sex all he wants on his break because his inevitable death on an operation will absolve all his past sins.

That’s the gospel that “Papa Noel” Zerkani preached, according to his sentencing documents, and he offered easy redemption from a life of crime and low-rent hedonism. The only catch, of course, is this redemption will often end in murder, or at best, a pointless death in the service of what most people consider the ultimate nihilism. It’s not simply that ISIS offers redemption to a criminal looking to change his ways; it’s that ISIS knows how to target criminals and turn them into jihadists. These young men don’t need to seek redemption — it seeks them out.

On an overcast afternoon in early March, the family and friends of Chakib Akrouh gathered together for his funeral at a cemetery in Brussels. The 25-year-old son of Moroccan immigrants had blown himself up in November 2015 alongside his childhood friend Abaaoud, five days after the Paris attacks, but it had taken months for authorities to identify him. The blast had shredded his body so completely that only after comparing Akrouh's DNA with his mother’s were investigators certain enough of his identity to release the remains to his family.

What those in attendance at the funeral didn’t know was that they were being monitored by a special unit of Belgian intelligence officers.

That’s because police hoped that tracking them would help lead them to Salah Abdeslam, one of the team members who had carried out the Paris attack but who did not blow himself up. The subject of one of the largest-ever manhunts in Europe, Abdeslam, for the past four months, seemingly had no trouble hiding out in Brussels — a city of just over 1 million people.

Abdeslam was no terrorist mastermind. He hadn’t trained in Syria, had only been entrusted with a minor logistical role in the Paris attack by Abaaoud, and had left behind a trail of evidence. There was CCTV footage of him before and after the attack, there were car-rental records, and the police had even arrested a friend who had picked him up from Paris and driven him back to Brussels — but despite all this, he remained at large.

“Some of these guys were pretty good but we were surprised it was taking so long to get Salah. He’d left clues all over Europe preparing for the Paris attack,” according to a Belgian cop involved in the search. When asked why Salah was so careless, the detective responded bluntly: “He was supposed to die, so why bother covering tracks on car rentals?”

Finding Abdeslam, police hoped, would also lead them to whoever built the suicide vests used in the Paris attacks, a critical concern. Homemade explosives aren’t that hard to manufacture, but making vests stable enough to explode at the right time is far from easy.

The Belgian authorities were at their wits’ end. But it was the funeral that provided the breakthrough in the hunt for Abdeslam. While normal wiretaps and mobile phone surveillance can be done by small intelligence and police services such as those in Belgium, grabbing huge amounts of phone data and electronic signal intelligence — and rapidly processing it — was beyond their capabilities.

The Belgian authorities knew they needed help, and had made a decision, which has not been previously reported, to involve an ally with a vested interest in dismantling a dangerous ISIS network: They called on the US National Security Agency (NSA).

“We had the NSA hit that phone very hard.”

“We called the American NSA before the funeral,” said one state security official, whose account was later confirmed by a Belgian police official. “As Edward Snowden has so helpfully explained to everyone, the NSA are the best at signal intercepts and [with their help] we grabbed all the information about all the phones present.”

The two officials described the scene at the funeral, where a known suspect was filming on his cell phone: “The guy is filming on a smartphone — that tells us he’s going to send that file to someone, right?” the security service source said. “We had the NSA hit that phone very hard.”

The NSA refused to comment on the operation, but a spokesman for the Director of National Intelligence forwarded an article in which James Clapper said: “The NATO Alliance faces an increasingly complex, diffuse threat environment. Consequently, we are always striving toward more integrated intelligence to stay a step ahead.”

On March 15, just a few days after the funeral, Belgian police made a move based on the information they had garnered from the NSA. Alongside French investigators, they raided an apartment in the Brussels neighborhood of Forest. It ended in a firefight; four officers were wounded and one of the occupants was killed. But investigators learned from fingerprint and DNA evidence that Abdeslam and a co-conspirator, Mohamed Abrini, had been there, although the two men escaped over city rooftops during the shoot-out.

It was an embarrassing blow to the investigation, but the NSA was at least now helping the Belgians track the suspects via their phones. Having lost his safe house, Abdeslam was forced to move around and communicate with people outside his rapidly shrinking network. Abdeslam and Abrini called a friend searching for a new place to hide out.

That’s when, according to the military intelligence official, they got him: “Finally … we have this asshole.”

“He went to ground in the only place he knew well,” said the official. “Molenbeek.”

Within days, Abdeslam was arrested just 100 meters from his childhood home in Molenbeek. But amid the relief at his capture, police remained worried: The bomb maker for the Paris attacks remained at large.

Police officials around the EU described themselves as being unable to sleep until they had the bomb maker in custody. DNA and fingerprint evidence on one of the abandoned vests used in Paris pointed to Najim Laachraoui, a 24-year-old Belgian-Moroccan engineering student who had disappeared into Syria to fight for ISIS in late 2013. Yet another petty criminal turned jihadist from Molenbeek, Laachraoui was considered by police to be more dangerous than Abdeslam, and far more intelligent.

In the hours after his arrest, Abdeslam initially cooperated with police as he was treated for a gunshot wound to his leg, identifying photos of Laachraoui and two gangster brothers known for trying to join ISIS in Syria, investigators at the time told me. He warned that a plot to bomb Brussels was underway. The target date, according to Abdeslam, was the day after Easter, two weeks away.

But just four days later, bombs tore through Brussels Airport and a metro stop servicing the European Union headquarters complex. DNA evidence concluded Laachraoui and two brothers, Khalid and Brahim el-Bakraoui, died in the blasts. Two more suspects, including Abrini, evaded police until they were arrested on April 8.

The aftermath of the attack gave counterterrorism a series of leads to follow, resulting in a flurry of arrests across France, Germany, and Belgium that authorities claim disrupted a major plot. On March 25, French police arrested Reda Kriket, a French national convicted in Belgium as part of the Papa Noel cell in Molenbeek, in an apartment laden with explosives on the outskirts of Paris. Authorities refused to comment on whether NSA assistance led to his arrest, but French officials described his plot as advanced.

Guns are supposed to be hard to obtain in Europe. Strict laws, especially compared with the United States, tightly limit their sale — a would-be killer can’t just head to a local Walmart and purchase an AK-47.

But automatic weapons have played major roles in the attack on the offices of the satirical magazine Charlie Hebdo in January 2015, the massacres in Paris, as well as in failed attacks on a church and a high-speed train. Police have recovered them in raids on multiple locations in Belgium and France, including the Forest safe house where Abdeslam was hiding shortly before he was caught.

In mid-March, I met with “Eddy,” an Albanian man in his forties, at a bar about a mile from the central Brussels tourist district. It was a small, shabby place; red fluorescent lighting clashed with the green vinyl barstools. It was the sort of bar frequented only by a handful of regulars, some of whom had met to drink beer and Balkan schnapps while music videos blared out from TV screens. Everyone was smoking in open defiance of EU regulations. They appeared unused to strangers coming in for a beer.

Slim, but with an emerging middle-age paunch, Eddy slipped comfortably between English, French, Romanian, Serbo-Croatian, and Albanian. He gleefully described his family as “big and notorious” in the former Yugoslavia, which he fled during the Balkan Wars of the 1990s.

Within a few years of arriving in Western Europe, Eddy and his family had set up a variety of “import-export” businesses in Brussels, drawn to its central location in the heart of Europe and because of the ease of entering illegal markets compared with the Netherlands and Germany, where older, more deeply entrenched gangs run the show.

“Brussels is sort of wide open for business.”

“Brussels is sort of wide open for business,” he said. “Everyone is here, but nobody is in complete control of business. It’s considered neutral ground because it’s so close to the big ports and so much of Europe.”

“The cops are really hopeless [in Brussels],” he said. “Changing neighborhoods if you’re wanted for something is usually enough to get away, because there’s so many different police districts and the whole government is disorganized.”

And if it’s a serious charge, you can always jump off to Paris, Antwerp, Berlin, or any of a number of large cities easily accessible by train without showing any identification, he pointed out.

“I love Schengen — it’s the best thing to ever happen to businessmen like me,” he said of the European treaty that allows for virtually free travel between EU member states to the delight of businesses, tourists, and criminals alike. It made me laugh because a European cop recently had told me the same thing: He loves the visa-free travel of Schengen while on holiday, but at work it’s a constant obstacle to investigations.

The Balkan Wars left the former Yugoslavia and Albania awash with weapons from Cold War–era stockpiles, poorly monitored by corrupt law enforcement, he said. “To get guns, drugs, even people from the Balkans or Turkey into the EU, you’ve just got to get past maybe one border post before you’re free,” he said, describing the only difference between Austria and France as “a trucking matter.” Investigators of the Paris attacks — as well as the Charlie Hebdo attack — have said in both cases that the automatic weapons used came from the Balkans or Eastern Europe via Brussels.

Guns, heroin, and human trafficking follow the overland routes, but cocaine comes through Rotterdam and Antwerp, two of the huge ports nearby, according to both Eddy and police detectives. “You just get it off the ship,” Eddy said. “You always lose some [to police], so you just send more. Anything that gets through, you just charge more to make up what you lost.”

This breakdown of the European underworld was interesting, but didn’t seem to immediately connect to ISIS and how it recruits would-be militants. That was until Eddy started explaining the ethnic hierarchy of transnational gangsters in Western Europe.

According to him, the North Africans of the Netherlands, Belgium, and France are close to the bottom of the drug-trafficking networks — which tend to be run by Italians, British, and South Americans — particularly immigrants from Suriname in the Netherlands.

“These idiots who become terrorists, they’re just the small-time guys — maybe they’ll buy a car or something,” he said. “They sell each other some hash or coke, sell on the street to people, get arrested fast. Maybe that’s why they go to Syria … they’re not able to become rich gangsters.”

“Albanians are usually in the middle,” he joked. “We’re the enforcers because nobody fucks with Albanians.”

“These idiots who become terrorists, they’re just the small-time guys ... They sell each other some hash or coke, sell on the street to people, get arrested fast. Maybe that’s why they go to Syria ... they’re not able to become rich gangsters.”

I agreed to return to Brussels in the near future so he could prove how easy it would be to find an automatic weapon in Belgium. He quoted a price of between 3,000 and 4,000 euros (about $3,300 to $4,500), depending on the condition, model, and amount of ammunition and clips included.

He knew I wasn’t actually buying, but said it wouldn’t take much effort and that I could photograph the weapon if I wanted.

Ten days later, though, the bombs exploded in Brussels; shortly afterward, Eddy’s mobile phone stopped working. But his claims about the scattered nature of the Belgian police forces rang true with European law enforcement officials.

“Brussels has 19 administrative police districts that operate independently and three separate administrations for the government, NATO, and the EU,” said one of the Belgian cops involved in hunting Abdeslam. “And our government is deeply divided between the Dutch and French, so there are parallel bureaucracies for everything on the local level and dysfunction at the highest level. No wonder guys get missed.”

He was talking about the string of mistakes that police made monitoring the Brussels cell: One local official had been told the house where Abdeslam was finally caught had ties to the Paris attack, but failed to send the information up the chain of command. Another police officer visited the bomb factory — a central Brussels apartment where Abrini, Laachraoui, and Bakraoui caught a taxi to the airport on the day of the bombings — on at least two occasions because neighbors repeatedly reported a terrible chemical smell. But with at least 470 Belgians known to have gone to join ISIS in Syria, and hundreds more either on watch lists or indicted for various plots and cells, the Belgians were already overwhelmed and appeared unable to process this information.

This was also happening in a country that in 2011 set the world record for failure to form a government after an election, taking 541 days. The previous record of 249 days had been held by Iraq.

The jihadi problem, however, goes much further than the Belgian dysfunction, according to EU experts, spies, and law enforcement officials.

“Coordination by law enforcement when there’s a specific arrest warrant or manhunt is pretty good,” according to a high-ranking police official in an EU country, who works on terrorism and organized crime cases. (He is not authorized to speak openly about the matter to the press.) He said cooperation between EU member states also depends on the severity of the crime.

The problem, according to an official with the French Defense Ministry who has worked on a wide range of intelligence matters, from organized crime to nuclear proliferation to terrorism, is the age-old concern about agencies being reluctant to share information without a very specific reason.

“You’ll never get information to help you build a picture from anyone,” he said. “Sometimes you can’t get that from your own agency.”

The official, who is so restricted from speaking to the press that he wouldn't let me identify myself as a journalist when I visited him in his office in a French military compound in Paris, described a situation in which major countries will share information to further their own goals.

“Liaisons sit in each other's offices from the major powers, the UK, the Americans, the French,” he said. “If the Americans get specific intercepts about a plot in France, it’s easy to cooperate.”

What’s impossible for the EU to fix, he argued, is a system where anyone can move across Europe without showing identification, but the police and intelligence services remain nationally focused. And the current system, where centralized databases at Interpol and Europol are supposed to flag the movements of fugitives, relies on the individual member agencies to do the actual police work.

“Europol and Interpol are desks that file notices,” said one EU detective with a long history in organized crime and terror investigations. They serve as clearinghouses for warrants and notices, but local police often lack an incentive to check on warnings from other countries unless it applies to a case of their own.

And even as the EU dismantled much of what had previously seen as the hallmarks of a state — border and immigration controls, a national currency and reporting regulations, monitoring trade in goods and services — it didn’t replace these mechanisms with any unified oversight. The removal of all these regulatory obstacles have been a boon for all business and international activity, both legal and not.

Fixing it would require national institutions — law enforcement, the military, and intelligence services — to give up some local autonomy in favor of further integration, something both the current political dynamic, as seen by the UK’s vote to leave the EU, and the entrenched mentality of the security establishment make very unlikely.

“No intelligence service in its right mind will regularly share intelligence with 27 other countries, because then it stops being intelligence if everyone else knows about it,” the French official said.

“Share one-on-one for a specific case, like France and Belgium on these terrorists? Sure, now that people are dead. But remember the biggest problem here is we’re all still spying on each other inside the EU.”

On a quiet evening this spring, a few weeks after the bomb attacks in Brussels, I visited Molenbeek. I’d spent a lot of time in the area over the previous weeks, but always in the company of translators, activists, and other journalists, and I felt frustrated at the impossibility of getting a sense for the place during such a tense time.

Despite its common portrayal in the international media as the dirty heart of terrorism in Europe, Molenbeek is a tidy, working-class neighborhood. But weeks of military-style raids and arrests by SWAT teams had cast a chill over the area. That night, the streets were quiet.

But on one corner, I found two young men smoking pot. They seemed bemused by a journalist walking around by himself looking for people to chat with.

Zak, 21, was skinny and scruffy, bearded with baggy, oversize clothes and a backwards baseball cap. He said he was a stand-up comedian — and claimed to have a YouTube following — and, in the words of his buddy Brahim, “is an idiot.”

“We don’t call it Daesh here. We call it Dawlat. The State.”

Short-haired and clean-shaven, Brahim was 23, muscular, handsome, and more serious than Zak. He had recently graduated from university as a civil engineer. They were both unemployed, and Brahim said his prospects didn’t look good unless he lucked out on a civil service exam.

Zak proceeded to roll another joint while Brahim questioned me about why I was reporting on ISIS and Molenbeek. I tried to explain in a general sense, but he interrupted me.

He pointed to the ground: “No! Why are you here? Here in Molenbeek?”

“Nobody will talk to you because they will resent that you want to talk to them about it,” he said, in a mix of English, French, and Arabic. “The young guys will think you’re a cop or CIA and the older people are just sick of it all. But why did you choose Molenbeek as a place to figure this out?”

He and Zak were stoned and sort of enjoying the conversation now, so I pointed out that around 80 young people from within one kilometer of where we were standing had left for Syria to join “Daesh,” using the Arabic acronym for ISIS, considered by the group’s members to be insulting.

“We don’t call it Daesh here,” Brahim answered, puffing on the joint. “We call it Dawlat,” directing me to use the proper Arabic term. “The State.” ●

CORRECTION

Abdelhamid Abaaoud and Chakib Akrouh died in a raid five days after the Paris attacks. An earlier version of this article erroneously said they died three days after the attacks.